The 1985 Annual Report marked the third year of the Railways Corporation, but was also notable in marking the first full year of full competition for land haulage of freight. Also notable was the beginning of the major restructuring of the Railways Corporation business following the Booz Allen report into the future of the railways. November 1984 also saw the end of the price freeze following the election of the Lange Government in July 1984.

The annual report below has a lot of images of railway staff in various situations, as well as text and data on the numbers for the year.

In 1985, the Corporation reported a financial loss of just under $20m (that is after receiving Social Services subsidies from the Ministry of Transport at a total value of just under $69.9m for passenger rail services, certain branch lines and some uneconomic road services). Social Services subsidies were down nearly 19% on the previous year.

It did report an operating profit of $2.9m. It had staff of 18,213 down by 935 on the previous year (Kiwirail has around 4,500 staff today). While road services and ferry revenue were up, rail revenue was down.

Rail freight tonnage remained similar to the previous year (increase of 1% in net tonne kilometres although total tonnes hauled was down slightly), but revenue down 8% due to the price pressures of competition. Average distance hauled was 307km.

The major restructuring evident in this report is consolidating the organisation into three businesses:

- Freight

- Passengers

- Property

- The launch of Doorrail, offering door-to-door delivery of goods, mode neutral. So freight would go from customer to end user.

- Sale of the two oldest Cook Strait Rail Ferries (Aramoana and Aranui) after their replacement by Arahura, noting only 4% of sailings were interrupted by weather, industrial action and urgent repairs. Also noted was increased competition on Cook Strait.

- Continued work on electrification of the North Island Main Trunk line

- Wagon fleet reduced by 5% (to haul similar amounts of freight) as did the locomotive fleet (predominantly due to scrapping some shunting locomotives and tractors).

- Earlier predictions that competition would mean Railways losing "small-lots" of freight and keep mainline bulk and large scale shipments were wrong, with road freight operators focusing on the larger volumes, not the small ones. This had stretched the Corporation's resources in sales and marketing.

- $8m worth of land sold, mostly residential to staff in Railway's staff houses. Noting the central Hamilton property development scheme (built on top of the former underground railway station in Hamilton).

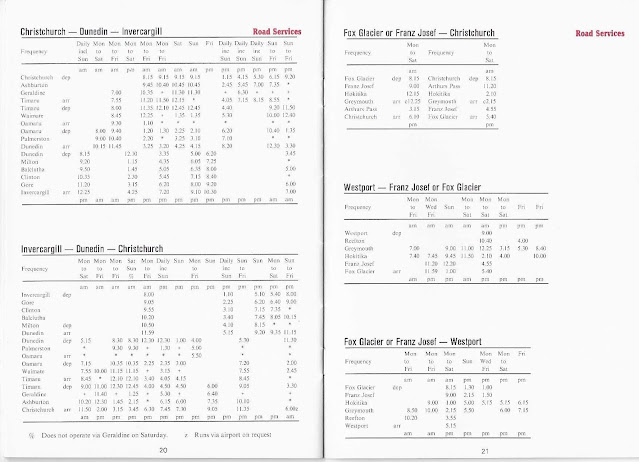

- Passenger business noted the opening up of competition to new road coach services, which saw Road Services launch new routes, with new Auckland-New Plymouth, Auckland Napier- Napier-Bulls and Picton-Christchurch services). Success of new Volvo coaches for comfort and reliability was noted. It was also noted that catering services were provided at 19 locations across the country, noting facilities at most locations operated at unusual hours for short intense periods of activity (e.g., serving trains with no on-board catering that stop for refreshments. At the time this included Taihape, Palmerston North, Napier, Kaikoura, Springfield and Otira).

- Book value for the assets was around $925m, which was essentially original cost minus depreciation, and bears little relationship to the market value of those assets.

- Long distance passenger rail patronage dropped by 11% compared to the previous year.

- Suburban passenger rail patronage rose by 5.6% compared to 1984 (continuing to reflect the improvement in reliability and comfort with the Ganz Mavag rail units in Wellington)

- Long distance passenger road services patronage dropped by 4.5% compared to the previous year.

- Suburban passenger road services patronage increased by 1.9% compared to 1984